For the last three months, Jervis Lyonga has been commuting to Bishop Rogan College, an all-boys school in Cameroon, to volunteer teach the Human Dignity Curriculum (HDC).

“The trip is only fifteen minutes,” he says modestly, before eventually admitting that “the roads are not the best, given the security challenges . . . and the rainy season . . . but if you’re lucky enough to get a taxi . . .” He typically leaves his home around 8am to be on time for his 11am class.

Jervis sits quietly in front of a wall of books. He’s a student himself, pursuing his master’s degree in conflict resolution, international law and human rights. His country is in a state of unrest, with violent clashes between separatists and the Cameroonian security forces.

“I don’t know how to describe the root causes, but there’s a lot of regional inequality in the two English regions as compared with the French. You don’t know what is going to happen. You don’t know who is responsible. You don’t know if you’re safe. But presently I would say it’s relatively calm especially in the educational sector, as opposed to when it started in 2016.”

Jervis joined World Youth Alliance in 2021. He completed the Certified Training Program (CTP), becoming a trainer of other members both regionally and globally, before doing the Advocacy Academy during an internship with the regional office in Nairobi. “I had HDC in mind as a way to give back to my community. I wanted to do more.”

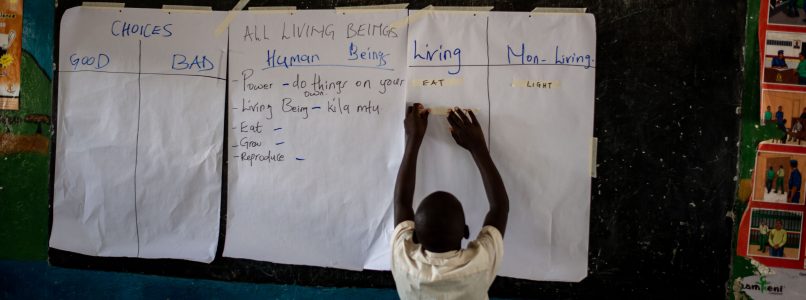

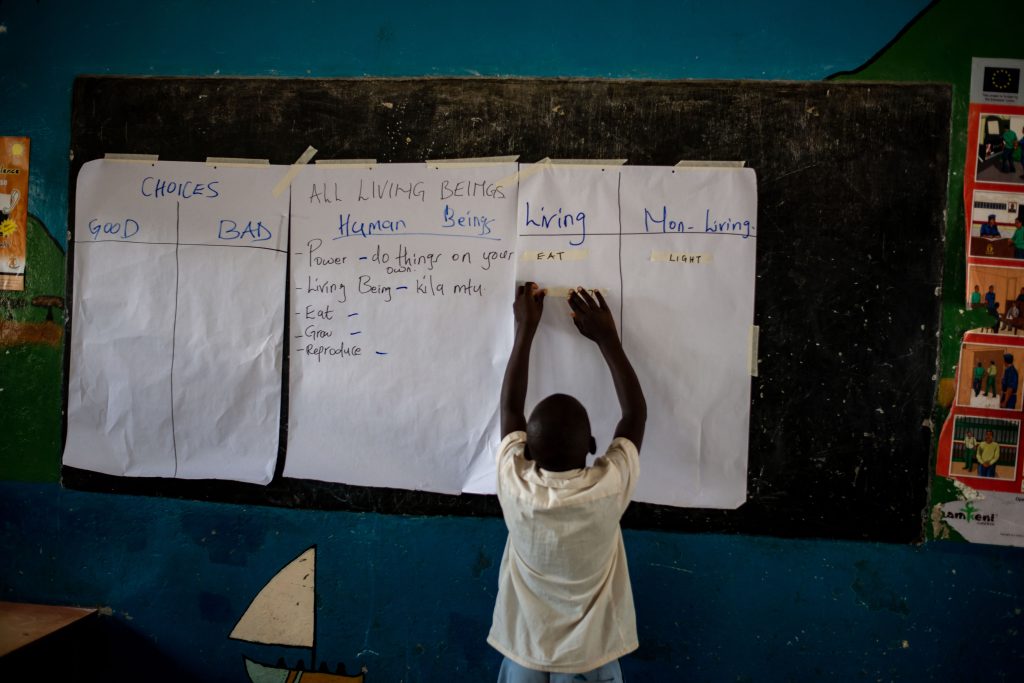

It takes the right place and the right principal to implement the Human Dignity Curriculum. Jervis found both at Bishop Rogan College: “Initially the principal wanted me to teach HDC to the whole school, but due to scheduling, I ended up teaching just 40 students. The first day was . . .” he exhales and smiles. “I wrote human dignity on the board and asked students to simply raise their hand if they had human dignity, were important and loved.” Only five students raised their hands.

“I was a little bit shocked,” Jervis admits. “But this one question got the class moving.” At the end of the lesson the students assigned themselves homework: “They wanted to write about their personal purpose, in reaction to the question of personal importance.”

In lesson two, there was silence when Jervis read the definition of treating persons as objects aloud: “using persons for personal pleasure or benefit.” “They knew what it meant,” he says, “They were real philosophers about it.”

Jervis led his class in discussing Martin Buber’s classic text, I and Thou. “We discussed questions that tied deeply to their day to day lives. HDC bridges that connection between what they have inside of them and what their expectations are for themselves. I think because it’s the one academic class that’s ‘all about you,’ the HDC fits well into their daily lives and students share their feelings.”

But it was the lesson on Freedom that really changed the tone in the classroom.

Jervis asked the students if they thought they had freedom. They did not think they did. “We discussed the freedom to be here at this school or this choice or that to break rules . . . We discussed this for a long time.” Then, after reading Viktor Frankl, “about how everything can be taken away from you, and yet in that moment being able to somehow decide your attitude . . . It changed everything,” Jervis says. “Their approach to things was different after that.”

By week five, students would be looking for Jervis in the halls. “They were like, where were you? When are you coming back to school? I said, don’t worry, I told you I’ll be back! They loved it. Every day they were following up, asking questions from the previous lessons.”

Jervis included Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” song in the lesson on The Power of Art, to further the discussion: “I said listen to the lyrics, what does it say about freedom? Is it freedom for excellence or indifference?” The Human Dignity Curriculum had given these high school students a vocabulary for thinking philosophically about their lives and the world we inhabit.

He created quizzes and evaluations so that the students would take the material seriously, since there is no formal grading for HDC. “It was a rich experience for the students, as they were really making connections between what they were learning in other classes and these deeper questions in the HDC.”

Before leaving for Christmas break, the students received their HDC graduation certificates in a closing ceremony in the school auditorium, attended by teachers and parents. If class scheduling permits, the hope is that in the new year, the juniors at Bishop Rogan College will start HDC next.

“People think that human dignity is the same as human rights. But it isn’t. Human dignity is the basis for human rights,” says Jervis. And so, the Human Dignity Curriculum helps students learn something about themselves. As for his personal experience, “I’ve learned a lot,” he says. “All of this has changed my scope. And I think for me, my field of studies is not unrelated—it has helped me a lot in terms of my personal development.”

For Jervis and his students, that development is well worth the three-hour commute and extra class.

WYA Staff Writer, January 2024